Naomi Wilzig Collection Blog

Lesbian Erotic Art? - Representations of Female Same-sex Sexuality in the Naomi Wilzig Collection

Written by Megan Brailey (November 2021)

During my internship in the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection project at Humboldt University I became interested in writing about the representation of female same-sex sexuality in erotic art because of the way the artworks I encountered both reflected and refuted usual representations. After conducting some preliminary research, I realised how little I was able to articulate the intricacies of the representation and discrimination of lesbian women. In this blog post I will discuss the production, representation, and categorisation of lesbian erotic art. I will first address the general lack of self-authored lesbian art, then the perception of lesbian sexuality and thirdly the terminology that is used to talk about female same-sex sexuality in art history. When I refer to lesbian art in this blog post, I am referring to visual art, mostly paintings and lithographs, depicting female same-sex sexuality and specifically the representation of lesbianism in erotic and sexually explicit art.

Representations of Explicit Female Same-Sex Sexuality: Erasure and Hyper-Sexualisation

Women in general, and especially queer women, for a long time did not have access to the arts and the means of artistic production. Systems of patriarchy and heteronormativity until today often discriminate homosexuals socially, culturally, and legally. Throughout history convictions about what is normal and natural in relation to sexuality meant that heterosexuality was the norm and homosexuality was deemed sinful and a punishable crime or a pathological illness. Additionally, until the 20th century woman did not have the right to own property or control their wages[i], and didn’t have equal pay or rights to men[ii]. Therefore, it was not only difficult for lesbian women to produce art, but those representations were also either hidden or kept private, systematically destroyed, or presented in such a way by collectors and curators that negated any notion of lesbianism.

But lesbian erotic and sexually explicit art was difficult to produce not just because homosexuality was taboo, but also because explicit sexual content in general was unacceptable in both the public and private view. Especially as for the most part of European art history the arts were sanctioned for and commissioned by the church and the aristocracy. Partially because of (queer) women’s difficulties accessing the arts, there are few historical examples of sexually explicit representations of female same-sex sexuality which were produced by queer female artists[iii][iv]. Additionally, it is often hard to identify erotic artworks by lesbian women because erotic art was often produced under a pseudonym, or the artists remained anonymous.

This erasure and lack of representations of female same-sex sexuality by lesbians is paradoxically accompanied by a hyper sexualisation and fetishization of lesbianism in erotic art and popular culture. As Jamie Jenkins shows in her analysis of the US Cold War period, anxieties about gender norms and sexuality caused moral panics whilst simultaneously erotic lesbian fiction was mass-produced for a widely heterosexual male audience. This is in tandem with the commercialisation of sex and women in advertising for consumer markets[v][vi].

Most of the representations of female same-sex sexuality in visual art were made by men for heterosexual men, which is why many scholars highlight that they conform to the heterosexual “male gaze”. The male gaze can be broadly defined as representing women from a heterosexual male perspective that usually regards women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer, and so conforms to beauty standards set by heterosexual men. Meaning that, in the context of erotic art, most of the representations and terms we have for female same-sex sexuality are men’s ideas of what female sexuality looks like.[vii] This leads to misrepresentations of lesbian relationships and often hypersexualises and heterosexualises them, in the sense that lesbian sexual pleasure is seen as something intended for the pleasure of men rather than for the women involved. This relates to the patriarchal bias, wherein men are often seen as the “subjects” of sex, whilst women are often the “objects”[viii].

Representations of Female Same-Sex Sexuality in the Naomi Wilzig Collection

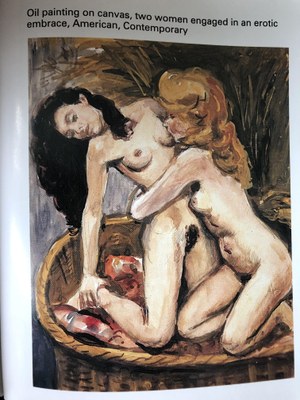

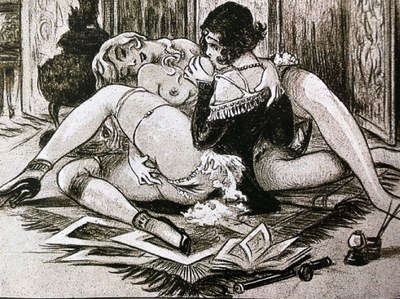

Of around 1600 artworks in the Naomi Wilzig collection that I reviewed, approximately 72 artworks depict representations of female same-sex sexuality.[ix]. Of these 72 artworks, 34 are sex scenes of female couples (image 1), 25 artworks show group sex scenes involving one man (or more) surrounded by more than two women, where the women were at times having sex with one another but are usually centred around the man (image 2); 5 artworks show group sex scenes involving only women; 6 artworks show lesbian sex scenes that include a male voyeur (image 3) whereas only 2 artworks depict lesbian sex scenes with a female spectator (image 4).

Image 1 (left): Lithograph by Paul Emil Becat, c.1930.

Image 2 (right): Painting, artist unknown, 2000s.

Image 3 (left): Lithograph, attributed to Alfred Musset, from the book 'The Tales of Gamiani' or 'Two Nights of Excess', in 1833.

Image 4 (right): Lithograph from a portfolio titled 'La Folle Journee de Gaby d'Ombreuse' by Berthomme Saint-Andre. French, c. 1920.

It is notable that there are almost as many group sex scenes involving multiple women as sex scenes showing just lesbian couples without a voyeur. I interpret this quantity of group sex scenes depicting female same-sex sexuality with a man involved and the ubiquity of depictions of female same-sex sexual intercourse with a male voyeur as an example of the hyper-sexualisation of lesbianism for a male audience[x]. Most artworks were done by men, or the artist is unknown. Many artworks cater to what is acceptable to the heterosexual male gaze and the majority of the women represented are white and feminine in appearance. Interestingly there is one painting in the section about female same-sex couples that depicts a nude woman on a sofa with what the description calls a “butch hairdo” (image 5). There are some other exceptions to the heteronormative framing of lesbian sexuality such as the female voyeur to a lesbian sex scene (image 4) and for example a sex scene between three women and a trans* woman (image 6).

Image 5 (left): Painting, artist unknown, USA, c. 1950.

Image 6 (right): Lithograph from a portfolio by Jean Morisot (Jean De Sauteval), c. 1930.

Interestingly these exceptions as well as the majority of the artworks showing lesbian sexuality I found were from France from the 19th and 20th century. In France, especially during the decadent movement in Paris, lesbians were seen, despite being at the bottom of the social hierarchy along with sex workers, peasants, and bartenders, as representing “new models of sexual freedom”. As “Lesbianism – both the identity and the term itself – became part of the French bohemian, artistic underground”[xi]. Therefore, these images do not necessarily represent a lack of bias in French culture at the time but highlight how representations of the deviation from the norm and social realism were in fashion. It is telling that two of the French artworks (image 3 and 6) are from books which also represent other taboo scenes such as zoophilia.

Titling and categorisation

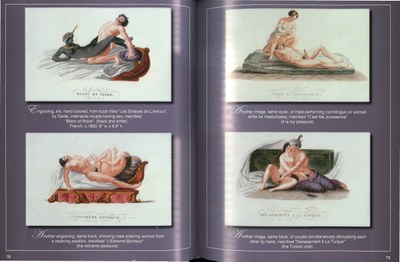

Art depicting female same-sex sexuality is often heterosexualised in the process of cataloguing, meaning that potentially homoerotic content is described with neutral titles and descriptions in order to erase explicit references to lesbianism.[xii] Additionally, there is often a general inconsistency in the cataloguing of erotic art because there is no clearly defined, specific terminology on sexuality in the arts. Whether and how the homoerotic content or subtext is recorded is therefore often dependent on the individual art historian or cataloguer. As in general society there is a distinctive lack of non-biased terminology to speak about homosexuality in a non-heterosexualised way. Often when lesbian sexuality is addressed it implies that any other sex than heterosexual vaginal sex isn’t “real” sex. See for example this mid-18th century French bronze statuette of two women on a chaise lounge, one leaning over the other as they engage in manual sex (image 7). The description in the catalogue reads: “two nude women embracing on a chaise”. Similarly, the description of another painting of a lesbian couple (image 8) states: “two women engaged in an erotic embrace”.

Image 7 (left): Bronze statuette with gold doré, French, mid-18th century.

Image 8: Painting, unknown, American, 1998.

The phrase “erotic embrace” is incredibly vague because an embrace can be intimate but not sensual or erotic. But the sexual practices depicted in the artworks could more precisely be described as “groping”, “kissing”, “masturbation” or “manual sex”. Likewise, lesbian sex scenes are frequently described as “sex play” or “sexual play” when women are engaging in explicitly sexual acts such as cunnilingus or fingering (image 9). The Collins English Dictionary defines sex play as: “erotic caressing”, “as a prelude to sexual intercourse, foreplay”.[xiii] Therefore, describing these depictions in this way trivialises sexual intercourse that is non-penetrative and non-heterosexual. This can be understood as projecting heteronormative expectations of sexual intercourse unto representations of female same-sex sexuality. I would propose that a less veiled and more precise language is necessary to describe lesbian sexuality is needed.

Image 9: Lithograph by Jean Morisot, c. 1930.

Final thoughts

Whilst writing this article, I felt myself lacking the vocabulary that is necessary to describe the intricacies of discrimination against lesbian women under systems of patriarchy and homophobia in capitalistic systems which benefit from both. Although most of the representations of lesbian sexuality in the Naomi Wilzig collection conform to heteronormative and hypersexualising norms, it’s worth mentioning that the fact that the collection even contains any exemptions from this norm at all is impressive if we consider the Western art historical canon. I am still spurred to research more and feel the overwhelming desire to promote more lesbian and queer artists in general, and to create and distribute more representations of female same-sex sexuality. The more diverse images of female same-sex sexuality there are from a wide range of sources – importantly also from women representative of this group – the more representative collections such as the Naomi Wilzig collection will be of the diverse and varied sexualities and sexual practices of lesbian women. This is not only important in order to counter the erasure but also because in my opinion there is a link between the portrayal of lesbianism in art and the day-to-day treatment of lesbian women today.

A contemporary artist that combats many of the issues I have described, who prefers to call themselves a visual activist rather than a visual artist, is Zanele Muholi. They state that: “most of the work I have done over the years focuses exclusively on black LGBTQIA and gender-nonconforming individuals, making sure we exist in the visual archive”[xiv]. In their art I see important themes of self-authorship and reflection, activism, and the necessity of representation. You can find more information about them here: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/black-artists-matter/.

Megan Brailey is currently completing her B.A. in English literature at Durham University, UK after studying a year abroad at Humboldt University, Berlin.

[i] The Harvard Business School, ‘Women, Enterprise & Society’. Women and The Law. https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/wes/collections/women_law/. 2010

[ii] Gert Hekma: A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Modern Age.

[iii] Ellen Oredsson: Lesbianism and Queer Women in Art History: Where Are They? http://www.howtotalkaboutarthistory.com/reader-questions/lesbianism-sex-female-desire-art-history/ 5. September 2016.

[iv] At the end of the 20th century and in the 21st century this has started to change also due to the democratisation of the arts, with art supplies becoming cheaper and the internet meaning that people can propagate their art without galleries and other institutions.

[v]Jamie Jenkins:Fear or Fetish? The Fetishisation of Lesbians in Cold War America. http://www.historymatters.group.shef.ac.uk/fear-or-fetish/ 20. January 2021.

[vi] See for example: Tom Reichert: The Erotic History of Advertising. Prometheus Books. 2003. For an excerpt see: https://aef.com/classroom-resources/book-excerpts/erotic-history-advertising/.

[vii] Ellen Oredsson: Lesbianism and Queer Women in Art History: Where Are They?

[viii] Gert Hekma: A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Modern Age. Introduction. Berg Publishers. 2012.

[ix] I say approximately, as I could only work with images of the art objects and not the objects themselves, and some depictions are ambiguous and unclear, and others are still uncatalogued.

[x] See Jenkins for more on the hyper-sexualisation of lesbianism and the idea of lesbians as nymphomaniacs.

[xi] Ellen Oredsson: Lesbianism and Queer Women in Art History: Where Are They?

[xii] How to Talk About Art History Blog

[xi] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/sex-play

[xiv] https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/black-artists-matter/

Kamasutra - More Than Sexual Positions

Written by Joan Ellingsgaard Kindberg (October 2021)

In the Naomi Wilzig Collection there are many different references to the Kamasutra: statuettes and figures described as being in “Kamasutra positions”, bracelets with images on the circumference with “Kamasutra scenes”, and temple pieces and sculptures with carved images of figures described as representing Kamasutra. See for example this Indian sculpture (Image 1) carved from a tree trunk which is said to be from around 1850 from either the Khajuraho or the Konarek temples which shows numerous nude figures engaged in various sexual acts and positions and which is described as “illustrating ‘Kama Sutra’ poses”[i].

During my internship in the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection project at the Research Center for the Cultural History of Sexuality at Humboldt University in Berlin I became interested in understanding what the Kamasutra actually is. What makes a sexual position a Kamasutra position? Is it even culturally and historically correct to make such a distinction?

In this blog post I will describe the history of the Kamasutra and its reception in the West and its unduly reduction of the Kamasutra as a sex handbook. For this I will first give an overview of the translations of the Kamasutra into English and then focus on the marketing of the Khajuraho temple site as a “Kamasutra” destination

What is the Kamasutra?

I do not have a distinct memory of when, or how, I got to know about Kamasutra. I just associated it with being “something about sexual positions”. Most likely, this view was influenced by countless Western mainstream media's portrayal of how Kamasutra can be used to enhance your sex life. Most modern translations and versions reinscribe an exoticized view of the Kamasutra and market it as a self-help guide to better sex.[ii]

Contrary to mainstream Western portrayal, the Kamasutra is not only a guide for sexual positions, but instead a text on how to live a pleasurable and desirable life in general. Kamasutra is a Sanskrit word composed by the word kama, which translates into desire, and the word sutra, which translates into thread. In the original Kamasutra, desire is defined as any kind of desire which can pleasure all your senses. It is estimated that the Kamasutra was written between the second and fourth century AD. Most often the Kamasutra is ascribed to the Indian philosopher Vatsyayana, however some believe that the text was compiled by several different texts, which could have had several authors[iii]. This version of the Kamasutra was written in Sanskrit, and at present there exist several translated versions and interpretations of it.

The Sanskrit version which is often attributed to Vatsyayana has seven different parts, all dealing with ‘how to lead a pleasurable life’ from different aspects. The first part is on general practices, the second describes in detail various positions for sexual intercourse? between heterosexual partners. The third part describes how a man can obtain a bride. The fourth is a text on which duties the wife has. The fifth part describes how you can have a relationship with other men’s wives. The sixth part is a text describing relationships with courtesans, and the seventh part is a text on the “secret formulae designed to ensure success in sexual activities”[iv]. A big part of the texts relates to the importance of using various art forms (dancing, singing, writing, painting etc.) to obtain different kinds of pleasures and desires. So, while there are many more aspects in the Kamasutra than mere suggestions for sexual positions, it is the second part on sexual positions which has become synonymous with Kamasutra. This reductive reception has a lot to do with the colonial history of India.

Translating the Kamasutra

The English orientalist Richard Burton is often credited for “discovering the Kamasutra”.[v] He was a diplomat for the British Colonial Empire and often referred to as a “traveler” or “explorer”, and was very interested in the erotica and sexual aspects of the countries he travelled through, Burton was part of the Kama Shastra Society, which published the first English translation of the Kamasutra in 1883 (at this time India was still occupied by the British colonial empire). Scholars are not entirely clear on who the members of The Kama Shastra Society were, but it seems to have consisted of a small group of English men. The aim of the Kama Shastra Society was to publish “erotica from the East for the sexual liberation of Victorian society”.[vi]

The 1883 English translation was titled The Kamasutra of Vatsyayana and has been heavily criticized by several scholars for being poorly translated, neglecting crucial parts and being a simplified and exoticized version of the original text. Among the several things which were left out were accounts of male and female same-sex sexuality (Only in the context when a man is not able to satisfy his multiple wives, female same-sex interactions were translated and included). Burton was in general very occupied with the idea of sexually liberating the female citizens of Victorian England (which was also the aim of the Kama Shastra Society) and this highly shaped the translation of the Kamasutra. Scholars such as Kumkum Roy and Jyoti Puri have, by comparing different translated versions of the Kamasutra through a feminist lens, highlighted how Burton’s translation both acknowledged women’s sexual pleasure, but at the same time framed it as something that needs to be normatively managed and regulated[vii].

According to Roy, Richard Burton’s translated version was, “probably the first version to describe the Kamasutra as a ‘work on love’”[viii], and despite the heavy critique of Burton’s translation, this version still influences most mainstream published work on the Kamasutra. The reception of the Kamasutra exemplifies that translating written pieces of work is not a neutral process, especially in a colonial setting. The Kamasutra is still entangled in a narrative of being a text for sexual liberation, which also shows in works done by Indian scholars.

A Hindi version of the Kamasutra, first published in 1911, which is often used by scholars today, has been criticized for promoting homophobic sex education, which focus more on absence of sex than sex. The interesting thing about this version and the critique of it is that the author, Pandit Madhavacharya, in his claim to translate the Kamasutra from an Indian nationalist perspective, ends up reinforcing a Western and simplistic view of the Kamasutra[ix]. Another example of a scholarly recognized translation is S.C. Upadhyaya’s Kamasutra of Vatsyayana: Complete Translation from the Original, which was published in 1961, has likewise received critique for underpinning the colonial legacies of the readings of the Kamasutra, despite the effort to distance itself from this problematic reading of it. While in a US context, the Kamasutra is portrayed often through mainstream, popular culture as “the sex handbook”, in India to a larger extent the Kamasutra is scholarly studied and debated. Puri is critical towards both, arguing that: “[...]both accounts reproduce questionable narratives of ancient India to promise sexual liberation from degrees of extant sexual repression; put differently, narratives of a liberal Indian/Eastern past and repressive present support the discourse sexual repression, with “the Kamasutra” as the mediating factor in these cases”.[x]

Exoticizing of the Kajuraho Temple Site

“Wood carving, temple mount, probably removed from a temple at Khajuraho, three deity type figures, Indian 18th Century, 17″ tall”[xi].

Another example of the exoticizing of the Kamasutra is the Khajuraho temple site, located in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India. Originally, the temple site consisted of eighty different temples, but today the temples of Khajuraho are a complex of twenty-two temples which have been listed as a UNESCO heritage site since 1986. The Khajuraho temples are estimated to have been built between 950 to 1160 AD, by the then ruling Chandela dynasty. The purpose for building these temples is still unknown, but there are several myths connected to the existence of them. According to one myth, the temples were constructed to visualize the loving relationship between the Moon god and an earthly woman. Some scholars argue that the temples and the Kamasutra sculptures were built to promote tantric sexual practices, (the sources I have on this, all talk about the temple site as one collective entity, although they are actually different), others argue that while the sculptures might be visual representations of tantric practices, the aim was instead to decrease sexual desire. Others again, argue that the temples were built as visual representations of the Hindu gods Shiva and Parvathi[xii].

TS Burt, a British officer working for the company Royal Bengal Engineers, is often credited for “re-discovering” the site in 1838.[xiii] Through Burt’s notes, it is evident that at least one of temples was still used for worship by the local community at the time. Some decades later, the Khajuraho temples were documented by another British officer, who described some of the sculptures as “highly indecent and disgustingly obscene”[xiv]. It is unclear whether the sculptures at this time were thought of as Kamasutra sculptures, but the narrative of these temples as ‘something highly sexual’ persisted.

After India’s independence in 1947, the then prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, initiated a promotion of the Khajuraho temples with the aim of attracting western tourists to the site. Since then, the tourist promotion of the temples has continued, and today it is possible to fly directly to the small city of Khajuraho from the capital city of Delhi. The Khajuraho temples are now heavily promoted as “Kamasutra temples” and have become a tourist site marketed to Indian and foreign tourists as a place of eroticism and “sexual liberation”. In 2015 alone around one million people visited the temples, in a town with a population of around 25.000[xv]. This is despite the fact that only about 10 % of the sculptures at the Khajuraho temples include explicit erotic representations. Other sculptures include for example visualization of teachers, students, dancers and musicians.[xvi]

This marketing of the Khajuraho temples as a site for Kamasutra, is another example of how the reductive view on the Kamasutra, influences not only western mainstream media but also parts of the tourism industry in India.

Ending Reflections – How to Describe and Display Kamasutra Objects in Museums?

“Promoted as a superior sex handbook, the Kamasutra promises pleasure and substance for inspiration. In effect, an unreflexive account of the Kamasutra reinscribes oppositions between the ancient East and the contemporary West, between contortionists and inspired couples, but also serves as a link between orientalist fantasy and female and male sexuality in the United States. To wit, the politics of historical, unequal relationships based on discursively constructed differences are elided”[xvii].

Even though the original Kamasutra had detailed descriptions on positions for heterosexual intercourse, I am still not sure whether to use “Kamasutra” to describe sexual positions – in museums or elsewhere. Because the Western notions of what Kamasutra means, is so entangled with orientalist narratives of the “exotic East”, I would argue that it is necessary to properly contextualize the Kamasutra instead of focusing on the sexual positions itself. This could for example entail the display of Kamasutra related art objects in an exhibition focusing on erotic orientalism and highlighting the implications of that, and/or to not focus solely on the erotic aspects but to place the Kamasutra objects in a larger cultural context. For this, I believe a constant focus on collaboration with people, and use of sources, which represent a different perspective than the white western narrative, is necessary.

Joan Ellingsgaard Kindberg holds a B.A. in Modern India and South Asian Studies (University of Copenhagen) and an MSc in Development and International Relations, Global Refugee Studies (Aalborg University, Copenhagen).

[i] The differences between tantric practice and Kamasutra sexual practices are not always clear in the texts.

[ii] For a critique of the colonial narrative of “discovery” see: Swetha Vijayakumar, “The Sacred and the Sensual Experiencing Erotica in Temples of Khajuraho,” Open Edition Journals (December 2017), DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/viatourism.1792 and Puri, “Concerning Kamasutras”.

[iii] Vijayakumar, “The Sacred and the Sensual”.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] The renewed interest in the temples and the erotic sculptures also led to a continued looting of the temples. It is estimated that between 1965 and 1970 more than 100 (erotic) sculptures valued at several million dollars were stolen and smuggled abroad. This could lead one to argue that objects from such temples should be returned to its original place. While that is also an important reflection, it is out of the scope of this blog post to deal with such a discussion. See Hamendar Bhisham Pal, The Plunder of Art, (Abhinav Pubns, 1992): 30.

[vi] Puri, “Concerning Kamasutras,” 605.

[vii] Wilzig, Forbidden Art, 77.

[viii] Ibid., 603-639.

[ix] Besides the English translation of the Kamasutra, the Kama Shastra Society also published English translations of Ananga Ranga in 1885, and Perfumed Garden of Sheikh Nefzaoui in 1886. For more on this, see Puri “Concerning Kamasutras,” 611.

[x] Ibid., 618.

[xi] Roy, “Unravelling the Kamasutra,” 165.

[xii] For more on this see Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History (Palgrave: London, 2000), 236-240.

[xiii] Puri “Concerning Kamasutras”, 606.

[xiv] See for example, Kama Sutra: The Book of Sex Positions or Kama Sutra, or The Ultimate Guide to The Ancient Art of Sexual Pleasure.

[xv] According to Kumkum Roy, this is a very common feature of Sanskrit texts written in that period. Kumkum Roy, “Unravelling the Kamasutra,” Indian Journal of Gender Studies, (1 September 1996): 155. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/097152159600300202.

[xvi] Jyoti Puri, “Concerning Kamasutras: Challenging Narratives of History

and Sexuality,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 27, no. 3 (2002): 157.

[xvii] Naomi Wilzig, Forbidden Art - The World of Erotica (Schiffer Publishing Ltd, 1998), 93.

Erotic Treasures? - Cataloging the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection

Written by Maya von Ziegesar (September 2021)

As an intern at the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection Project at the Research Center for the Cultural History of Sexuality at Humboldt University, my job has been to work on the documentation and to write new descriptions for the objects represented in the catalog Erotic Treasures. The ultimate goal of this project is to create an online database containing the entire Naomi Wilzig collection, complete with new descriptions, titles and searchable subject terms. This blog post lays out some of my thoughts about cataloging in general and Erotic Treasures in particular, including its organizational structure and the benefits and losses of doing away with this structure, issues I encountered with terminology and the practice of labeling, and the various ways I have tried to meet these challenges.

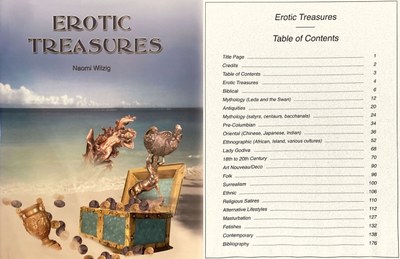

Left: Front cover of Erotic Treasures, 2005. Right: Table of contents of Erotic Treasures, 2005.

Erotic Treasures was published in 2005 and contains just over 300 objects from the World Erotic Art Museum. The objects are arranged into categories rather than strictly chronologically. Within each category, objects are presented individually with very brief descriptions and only basic information. There are no long contextual or interpretive texts (see images 3 and 5 for examples of the catalog’s format).

The organizational structure of Erotic Treasures carries meaning, and especially conveys a narrative of “progress.” We start with the origins, with Adam and Eve and the Ancient Greek and Romans, represented in the collection by a mixture of genuine artifacts and modern objects, often kitsch, utilizing Greek and Roman mythological imagery. Then we go to the pre-modern, which includes the non-Western: “Pre-Columbian,” “Oriental” and “Ethnographic.” Lady Godiva brings us back to the West and, in this progress narrative, ushers in modernity. In the final categories, from “Ethnic” to “Fetishes,” we reach the “others” within modern Western society. Together with the objects in “Contemporary,” these final categories complete the evolution of human sexuality, indicating the diversity and tolerance of modern, Western sexuality and sexual practices. In short, the catalog walks us through a narrative that begins in Western myth and ends in the Western modernity, treating the non-West and the pre-modern as stepping stones, and utilizing modern sexual diversity as a justification for defining the contemporary West as the pinnacle of sexual progress (see image 2). This problematic teleology of Erotic Treasures is reflective of a similar problem in the former permanent exhibition of WEAM, as pointed out by Katherine Sender in her article “Selling Cosmopolitanism: Same-Sex Materials in Museums in Asia, Europe and the United States”.[i]

The new online database in which the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection will be presented is non-linear, so the objects will no longer be grouped into these categories or arranged in this order. The narrative of Erotic Treasures, which places the non-West in the perpetual pre-modern and modern, liberal, Western sexuality as the apex of human sexual development, will be lost. In its new form, any information which used to be conveyed by the placement of the objects in the printed catalog needs to be either explained outright in text or will be lost. The idea that world history has culminated in Western sexual liberation can, uncontroversially I think, be done away with. But other elements of the catalog’s categorization are more complicated.

Erotic Treasures pages 78-9.

One complication stems from the fact that the collection as a whole skews heterosexual and white. For example, Erotic Treasures has 21 items containing depictions of Leda and the Swan, 11 of Adam and Eve, and countless of other white heterosexual couples. In an unordered mass, it would be hard to find the relatively few items depicting BIPOC or LGBTQI+ people. To be found, items like these need to be labeled, or else risk erasure. But by labeling, we risk ghettoization and essentialization, reducing objects down to their perceived “otherness,” and segregating them from the objects and bodies we normalize. If seven of the Adams and Eves are white, three ambiguous and one Black (as is the case in Erotic Treasures), then how do we ensure that this one depiction doesn’t get lost in a sea of whiteness, without also reifying the idea that to be Black is to be the “other” and to be white is the default or norm? Image 3 exemplifies both how items in the collection may be deeply problematic and how the language used in Erotic Treasures to describe the few objects which depict something other than white heterosexuality can be othering or ghettoizing.

Beyond the question of whether to label is the equally important question of how to label. In Erotic Treasures the language around sex is often veiled––couples are “entwined,” men are “tumescent”. Is the subject term of “homosexuality” too medicalized and “rimming” too informal? Why are there no thesauri or established cataloging terms for sex positions––should we just make up our own? The terms that exist for sexual practices are often oddly euphemistic incredibly loaded, or explicitly racist, colonialist, sexist, cis/heteronormative. For sex positions alone, “spooning” feels euphemistic, “scissoring” is loaded and problematic, “missionary position” is racist and colonialist, “girl-on-top” is heteronormative, etc. Resources like Homosaurus, the Planned Parenthood Glossary and the thesaurus of the Kinsey Institute were helpful, but we often found ourselves lacking the language to describe what we were seeing, and even complicit in various forms of linguistic violence.

Even now that the internship is ending, I don’t have answers to most of these questions. One ameliorative practice which I have found helpful in approaching this project is emphasizing the subjectivity and particularity of the collection, and in doing so resisting its claims to universality. The collection sometimes seems as though it is meant to show the eroticism of the world, the differences and similarities of human sexuality across all time and space. It is this claim to universalism which causes many of the collection’s problems: its narrative of sexual progress, its centering of the West, its plurality of depictions of white female nudes and white heterosexual couples. If we think of it less as a collection of “World Erotic Art,” and more as the Naomi Wilzig collection, then the collection has fewer pretentions of speaking for all people and can be viewed as rather speaking for one person, whose tastes, quirks and personal sense of eroticism are its guiding principle. Far from depicting the world’s sexuality, this collection very thoroughly depicts the artistic and erotic tastes of its collector who, as an older adult with no background in erotica and with a serious rebellious streak, amassed one of the largest collections of erotic objects in the world. Perhaps the most obvious example of the collection’s particularity is its disproportionate emphasis on Leda and the Swan, which is by far the most common subject in Erotic Treasures. Naomi Wilzig was a fan of Leda and the Swan, and even commissioned a portrait of herself as Leda (see images 4 and 5).[1]

Left: Naomi and the Swan by Karen Rosenberg (2004), Right: Objects depicting Leda and the Swan in Erotic Treasures, pages 18-19.

Naomi Wilzig had no background in art history or museum curation. She opened the museum as a way to share her passion for collecting erotic art, and in creating the galleries possibly emulated the practices of other museums at the time, attempting to create narrative from her highly idiosyncratic collection. However, there is evidence that she was open to listening to others regarding how her collection could be displayed in less problematic ways. In her article “Perverting the Museum: The Politics and Performance of Sexual Artefacts,” Jennifer Tyburczy shares an anecdote about how, once Tyburczy told Naomi Wilzig that she finds the cloistering of the section on homosexuality behind a black curtain to be problematic, Wilzig stood up immediately and tore down the curtain.[ii] I think the primary ameliorative practice that I was able to successfully develop in this internship is the tearing down of a curtain: the removal of the objects from the categories and narratives in which they were confined. As far as how to build up a new database, one which balances ghettoization with erasure, and is able to describe precisely without leaning on language that can alienate and dehumanize, we were able to take some steps in the right direction, but we still have a long way to go.

[i] Katherine Sender, “Selling Cosmopolitanism: Same Sex Materials in Museums in Asia, Europe and the United States,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 26 (1): 35–61.

[1] To the museum's credit, the name was changed from World Erotic Art Museum to Wilzig Erotic Art Museum in 2019 to more accurately reflect the galleries as the personal collection of its founder, rather than a representation of erotic art from around the globe.

[ii] Jennifer Tyburczy, “Perverting the Museum: The Politics and Performance of Sexual Artefacts,” Negotiating Sexual Idioms: Image, Text, Performance, ed. Marie-Luise Kohlke and Louisa Orza, Rodopi (2008).

Japanese erotic prints in the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection

Written by Thomas Pauvret (June 2021)

The Naomi Wilzig Collection, exhibited at the Wilzig Erotic Art Museum (WEAM) features several "shunga," a type of erotic print from Japan that differs in many ways from Western representations of sexuality, and has often sparked a great deal of interest among Western audiences.

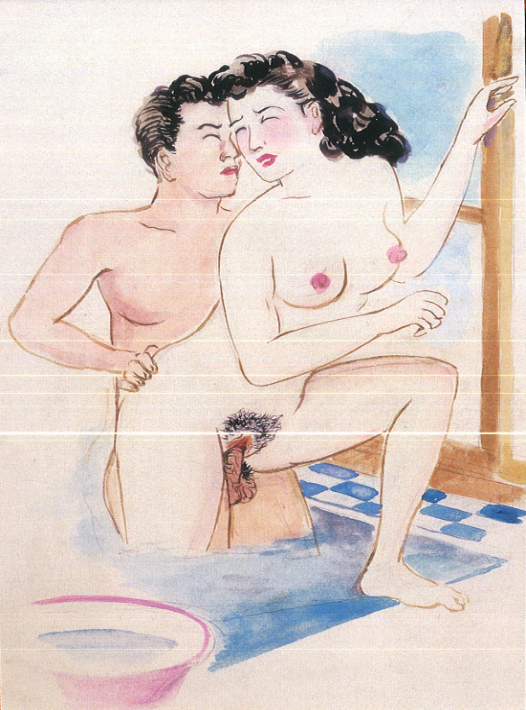

Shunga were produced since the 15th century and were inspired by Chinese pillow books. The word means “Spring pictures,” but they were also commonly called “laughter pictures,” which demonstrates a rather light approach to sexuality and erotic art. Naomi Wilzig collected dozens of these artworks between 1983 and 2005. This artwork from the collection is a classic example of shunga:

|

Shunga, ca. 1900, 10” x 8”

It shows a half-naked couple engaged in penetrative vaginal sex on the floor. Behind the couple there is a low table with upturned cups. It is a spontaneous scene of two people caught up in the moment, their cheeks red from the effort and perhaps from alcohol. Their layered clothing is in their way, making them appear to struggle to access the other’s body. The intention is to show an everyday scene. However, the proportions of the individuals are partially exaggerated, the penis and the vulva are larger than life. These images differ from their precise and realistic Chinese counterparts, which are meant as practical guides, demonstrating which sex positions are most beneficial for health. The positions in shunga are exaggerated, comical, disproportionate, and often anatomically impractical.

This image is from the “golden age” of shunga and was most likely printed with the woodblock technique and is in the ukiyo-e style, meaning "the floating world." The floating world refers to a certain aspect of Japanese life between the 17th and 19th centuries, very aware of the ephemerality and impermanence of existence of life and derived from a Buddhist concept. For this type of shunga the depiction of mutual consensual pleasure for both the man and the woman is important. See for example this print of a man stimulating a woman’s vulva:

|

Shunga, c. 1900, 10” x 8”

Sexual fluids are regularly depicted in shunga, signalling orgasm and its desirability. Shunga are deeply erotic, but as eroticism is not universal, the eroticism of shunga shows what Japanese people in the 17th through 19th centuries found erotic, including perhaps richly patterned kimonos, a certain curve of the neck, exaggerated genitals, and mutual sexual enjoyment. Additionally, although not as common as heterosexual scenes, some shunga showed two women or two men together. A common figure in the golden age of shunga are wakashū, an Edo period "third gender” composed of young adolescent boys who were dressed like women and were highly sexualized by both genders.

While Western erotic images were mostly made by men for the enjoyment of men and often only accessible to a select few, shunga were not taboo or hidden. They were enjoyed by both men and women, alone or with others, in public and in private. These Japanese images of sexuality would even be incorporated into a wife's dowry. To the surprise of many

Western observers, shunga was also believed to have some apotropaic properties, like protection from evil spirits and misfortune. Some records tell of warriors going to battle with erotic prints on their armour––what a sight it must have been!

It was not taboo to make shunga, and most of the great painters and artists of the time produced shunga. Hokusai for example, the artist of the "Great Wave of Kanagawa," also produced erotic paintings. Shunga sold well and, depending on the quality of their manufacture, their selling price could reach significant sums, especially if they were commissioned by a great lord. They were often embedded into scrolls or leaflets, printed in several hundred copies and sold in bookstores or borrowed from itinerant tradespeople. The use of woodblock printing allowed mass production and reduced the cost. A commoner could buy shunga prints for the price of a meal, while great lords could still ask painters for individual scrolls, painted with high-quality materials, gold and grinded seashells. The diversity of shunga’s audience perhaps also explains the diversity of the social classes represented, since most social classes and especially prostitutes from the “pleasure district” had their place in shunga.

Shunga began to fade during the 19th century and would almost completely disappear with the Westernization brought about by the opening of Japan in 1854.

Western influences

This taboo surrounding shunga in Japan, which continues until today, can be explained by a multitude of reasons, but it is impossible to ignore the responsibility of the Western powers in the 19th century. The growing influence of Western powers generated one of the fastest modernizations in history after the end of Japanese isolation in 1854. Over the course of half a century, the country passed from a pre-modern feudal society to a world superpower capable of defeating China and Russia.

To be recognized by the West, it was necessary to acquire Western technologies, but also to reduce the cultural distance and adopt a degree of Western values. The slogan "Enrich the country, strengthen the army" was accompanied by "Leave Asia, Join Europe." The things that most clashed with Western values were banned or reformed, including shunga, which shocked and fascinated Westerners. The Meiji government soon realized that the circulation of erotic images contributed to a Western perception of Japan as a "primitive" or "shameless" nation. A series of laws prohibiting shunga were passed between 1868 and the beginning of the 20th century. Shunga circulated with more and more difficulty, often functioning as novelty items for a Western market.

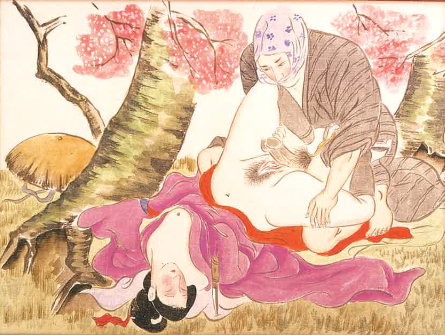

The adoption of Western values and elements of Western culture, in addition to the increasingly Western audience of shunga, can be seen in this painting in the Wilzig Collection, which was produced as a souvenir picture for US soldiers after World War II:

WEAM, c. 1950, 8” x 10”

Along with this cultural shift came the evolution of a style, that showed an increase in violent or non-consensual sex scenes which catered to a male gaze. Here is one image from the Naomi Wilzig collection in that style:

Shunga, c. 1900, 10” x 8”

This shift towards the male gaze was accompanied by an increased heteronormativity, since wakashū are completely absent from shunga produced in the late 19th century.

Collecting Shunga

Successive waves of interest in Japanese art hit Europe and North America since the opening of the country. Ceramics, lacquered boxes or prints were the pieces of choice, but imports also included shunga and small statuettes called netsuke, whose connotation can be sexual. Japanese erotic objects immediately fascinated the West and have been central to Japanese- Western relations since the 19th century. Commodore Perry, the American military leader who forced the opening of Japan, was offered shunga when he departed. Shunga have been found in the homes of Emile Zola, Picasso, Rodin, and George de Witt and in secret rooms of the British Museum and the Louvre. Interest in shunga is still vivid in the West, as exemplified by several recent exhibitions of Japanese erotic art, most notably at the British Museum in 2013, and by their extensive inclusion in the WEAM collection.

Shunga are works of art in their own right, and very representative of the society from which they stem. In their golden age, they were objects reflective of Edo period Japanese society, displaying a sexuality which was more lighthearted, mutually pleasurable and egalitarian. They immediately fascinated the West, in part because they were so different from the erotic objects Westerners were accustumed to, but in part due to their new Western audience, the popularity and authenticity of shunga declined alongside Japan’s accelerated modernization. Today, these are still controversial images, both in Japan and in Europe, but they also seem to be increasingly appreciated, collected and displayed.

For more on shunga, see : Timothy Clark, C. Andrew Gerstle, Aki Ishigami, Akiko Yano: “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art” British Museum Press, 2013.